by Valentina Valentini, ICG Magazine

Season 3 of Netflix’s rural family drug saga, Ozark, hits new visual highs (and dark narrative lows).

When Marty Byrde (Jason Bateman) walks into an office full of large glass windows, he’s the guy who will note the windows are south-facing, and the cooling bill will be about fifteen percent higher in summer. That same attention to detail is also what drives the behind-the-scenes team of Netflix’s Emmy-winning crime drama, Ozark, now streaming its third (and many would say its most visually ambitious) season. The series was created by Bill Dubuque and Mark Williams, executive produced by showrunner/writer Chris Mundy, with star Bateman also serving as an executive producer and director for nearly one-third of all shows produced so far. Season 1’s final episode earned Bateman his first directing Emmy nomination, along with a nomination for Local 600 Director of Photography Ben Kutchins, who has shot roughly half of all three seasons. Bateman went on to win an Emmy for the opening episode of Season 2, which Kutchins also shot. Guild Director of Photography Armando Salas came aboard in Season 2 to split the schedule with Kutchins. For this most current season, Kutchins shot Episodes 1, 2, and 6 while Salas shot 3, 4, and 7 through 10. (Manuel Billeter shot Episode 5.)

“There are so many things that have to go right for anything to be good,” observes Executive Producer/Writer Chris Mundy. “So, the attention paid to detail is everything. And that’s the beauty of being able to have two DP’s – one is always shooting, and one is always prepping. That’s a godsend for the director in prep, to have their DP fully [there with them] the whole time so they know exactly what the other one is thinking. I think it’s helped the show, and both of [our] guys are so good [at it].”

At its core, Ozark is a family drama, even if its elaborately staged crime segments (raised to a new level of ambition in Season 3) can overshadow the familial themes. When we first met Marty, his wife, Wendy (Laura Linney in an Emmy-nominated role), and their children, Charlotte (Sofia Hublitz) and Jonah (Skylar Gaertner), in Season 1, they were an average white-collar Chicago family who unwittingly became wrapped up in laundering money for a Mexican drug cartel out of the Missouri Ozarks. With Season 3, the Byrdes’ operation has grown, exponentially, even if their destinies are forever in jeopardy of being snuffed out.

From inception (Pepe Avila del Pino shot the pilot and Episode 2 of Season 1), Ozark has been a narratively (and visually) dark series. That means even the ostensibly “fun” moments – teenagers hanging out at a lake on a sunny summer day; wine and terrycloth bathrobes at a cozy bed and breakfast; winning the jackpot at a casino – are laced with violence and fear. “You know those joyful scenes in a thriller or horror movie, right before the hammer comes down, that trick the audience?” Kutchins posits. “Well, Ozark is a completely different meditation. It’s always bleak for our characters. We don’t allow them those joyful moments; it just goes from bad to worse.”

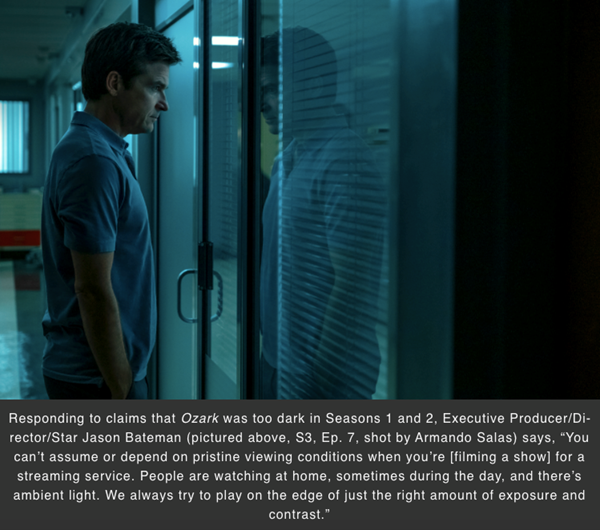

Though the tone in Season 3 is consistent with what came before, the creative team believed a slightly softer feel was appropriate for the story’s evolution. That was also a practical decision, since the darkness of the show wasn’t translating to all viewing platforms. “You can’t assume or depend on pristine viewing conditions when you’re [filming a show] for a streaming service,” Bateman offers. “People are watching at home, sometimes during the day, and there’s ambient light. We always try to play on the edge of just the right amount of exposure and contrast.”

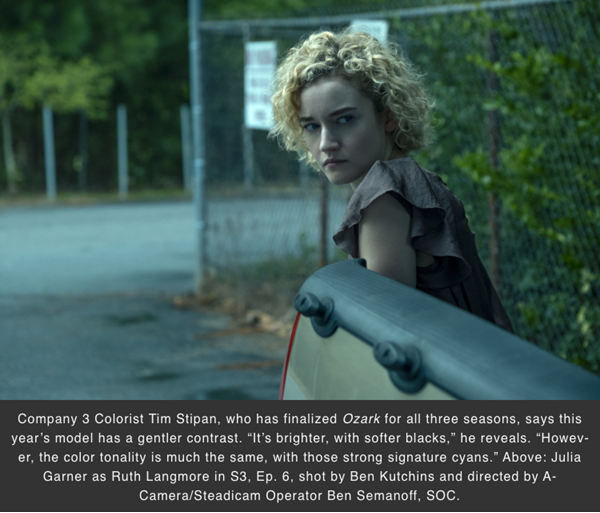

Company 3 Colorist Tim Stipan, who has finalized the look for all three seasons, adds that this year’s model has a softer contrast. “It’s brighter, and there are softer blacks. However, the color tonality is much the same, with those strong signature cyans.”

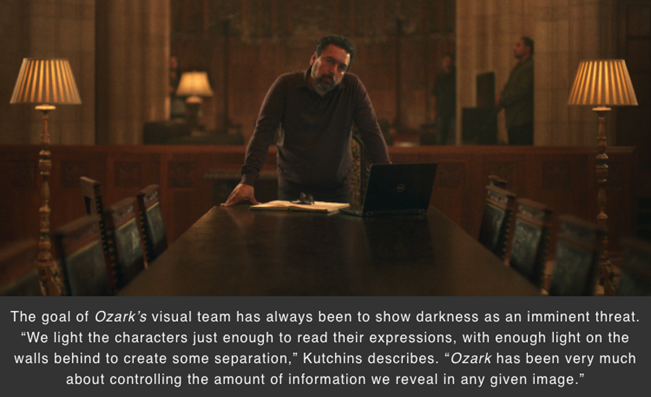

Kutchins (who came on right after the pilot) and Bateman wanted to create a world that was harsh and uninhabitable, despite its idyllic location on Lake Ozark – doubled by Georgia’s Lakes Lanier and Allatoona. The goal has always been to show darkness as a feeling of imminent threat; to do that photographically, Kutchins used the negative and positive parts of the image to create enough shadow to allow the audience’s minds to wander into what’s coming next without knowing what exactly that is – only that it’s bad.

“I light the characters just enough to read their expressions,” Kutchins describes, “with enough light on the walls behind to create some separation. Ozark has been very much about controlling the amount of information we reveal in any given image.”

While that approach was repeated in Season 3, Kutchins and Salas knew they had to evolve the look with the Byrdes’ progression. They’re doing business at the state-government level; there are new characters, like a sly forensic FBI agent, Wendy’s bipolar brother, and a spoiled son of a Mafia boss, and they’ve opened a bustling new casino, The Missouri Belle, a massive addition to the few sets the show used at Eagle Rock Studios Atlanta. (Most of the show has been shot on location in Georgia, doubling for the Ozarks.)

“My first question to Jason was about tone,” says Production Designer David Bomba, who, after replacing two previous designers, was the new kid on the block. “Ozark has a very blue-gray, overcast feel, and I asked if that was the direction I should pursue [for Season 3], and Jason was adamant I should not.”

Bomba, whose previous credits include the Sundance indie hit Mudbound (shot by Oscar nominee Rachel Morrison, ASC) and the Oscar-winning feature Walk the Line (shot by Phedon Papamichael, ASC), markedly expanded the show’s color palette. The designer took research trips to Rising Star Casino and Resort near Lawrenceburg, IN, and the Lady Luck Casino in Caruthersville, MO, before landing on a New Orleans riverboat theme with red and gold interiors. Having grown up in NOLA, Bomba expanded on what was familiar, modeling Marty’s office, the casino entrance, and The Marquette bar (the land-based parts of the casino) on older structures in the now-gentrified Warehouse District and the Napoleon House in the French Quarter.

He describes the Missouri Belle riverboat casino as fashioned after the paddle steamers that traveled up and down the Mississippi River in the 19th century. “Think Mark Twain, Victorian embellishments, opulent grandeur, elegant detailing, and warm light sourced by what would have been gas or oil-flamed fixtures,” Bomba reveals. “Jason suggested an overall red and gold scheme to contrast any other set piece that had been established in the series, so I ran with it. I was thrilled to expand the palette of the show.”

Salas says Bateman has always been intimately involved in the evolution of the show’s look. “The casino was going to have a very different feel from the majority of what we’d done before,” he adds. “ [We wanted] the casino floor [to feel] engulfing and sophisticated, like you could really be sucked into gambling all your money away. It needed to be a relief from the oppressive and cool [blue] world that we so often see.”

Kutchins and Salas wanted a wealth of practical lighting units in the casino set, and Bomba obliged, with a central gaming pit area and its ceiling coffers comprised of exposed carnival-like bulbs. Bomba also wanted antique brass chandeliers, sconces, and pendant fixtures – created by decorator Kim Leoleis and her team – both in the casino and the bar and entrance areas. Both Kutchins and Salas wanted more light, specifically additional softer, indirect sources as well as accent lights for the gaming tables in the central pit area. In the end, ninety percent of the casino was lit by practicals incorporated into the design.

“We went with a spot-lighting system for the table accents,” Bomba recounts. “For the alleys flanking the central pit that were lined with the slot machines, Joy Britt, our fixture’s genius from Edison Jackson’s electrical team, retrofitted some 40 ceiling-mounted star fixtures with RGBA-hybrid tape lighting. Another 30 or so ceiling fixtures were added to the second floor, retrofitted in the same manner. Joy also suggested using RGBA LiteRibbon with an architectural extrusion lens that resembled a neon strip.”

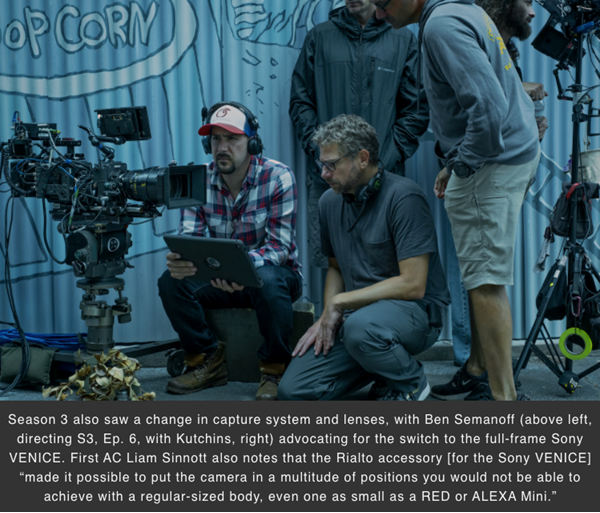

Season 3’s new tribulations for the Byrde family required Kutchins and Salas to dive ever deeper into the narrative rabbit hole, with full-frame capture and a shallow depth of field proving the best visual track. “Shooting full-frame brings the characters forward in the image,” describes Kutchins, who (at the suggestion of A-camera/Steadicam operator Ben Semanoff, SOC) switched, in Season 3, from the 4K Panasonic VariCam to the 5.7K Sony VENICE. “It’s almost equal to old VistaVision film, where you have these wide landscape shots, yet there is character in it, too,” Kutchins notes. “It manages to be both, simultaneously, and the characters come right into living rooms.”

The Sony VENICE offered Ozark’s directors of photography a much larger capture sensor, but in a small, lightweight body. Semanoff, who also has directed two episodes of Ozark, says he had used VENICE as A-camera/Steadicam operator on the Peter Berg feature Spencer Confidential (shot by Tobias Schliessler, ASC) and loved the form factor along with the Rialto attachment, which allows users to pull off the front block of the camera, essentially making it just a small housing for the sensor that is tethered via a fiber umbilical cable back to the main body to record the data.

“[Guild Director of Photography] Igor Martinovic and I pushed to use VENICE on [the HBO limited series The Outsider] with [actor/director] Jason Bateman,” Semanoff recounts. “I was a huge fan, as it has a great form factor for Steadicam and would facilitate the different locations we were looking at for Season 3 [of Ozark] – on the water, in the woods – some very remote areas. Although the ARRI LF was high on everyone’s list for image quality and color rendition [the ARRI LF Mini was not yet available], the VENICE met a wider range of our concerns.” First AC Liam Sinnott adds that the Rialto accessory “made it possible to put the camera in a multitude of positions you would not be able to achieve with a regular-sized body, even one as small as a RED or ALEXA Mini.”

The Ozark camera team also swapped out its lens package, using a Leica Noctilux and a set of Leica Summicrons and R-series. The Noctilux is a 50-mm lens rehoused from a still lens by True Lens Services. It opens to a .95 aperture, one of the fastest lenses out there, and it allowed them to shoot in extremely low light situations as well as isolate their characters during daylight exteriors. Switching to a large sensor, with a lens that opened the aperture more than a stop, did increase Sinnott’s challenges as a focus puller, as well as the visual aesthetic. Multiple camera setups required a diopter with whatever camera had a Summicron or Leica R lens to achieve the same shallowness as the Noctilux.

“Ben and Armando are constantly trying to push the look of the show,” Sinnott adds, “be it through shot design, exposure, or depth of field. A lot of the conversations concerning the use of the Noctilux revolved around isolating the characters. They wanted scenes with a single actor in wide shots to separate from the foreground and background and be the only element in focus within the frame. With scenes involving multiple characters, they wanted the ability to detach story beats and use the focus as a storytelling tool.” Kutchins adds that “as the Byrdes further isolate themselves from each other, we wanted to use this lack of depth of field to isolate them visually from one another.”

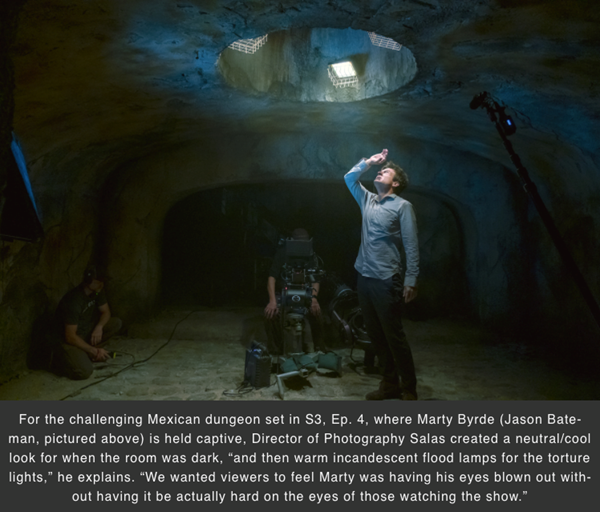

Salas cites an example from the opening moments of Episode 4 when Marty, having been kidnapped by the drug lord Navarro (Felix Solis) to Mexico, awakens in a dark cell. Shot in a series of three set-ups, “the camera is very close to [Bateman], experiencing the same disorientation that Marty is feeling,” Salas explains. “The background is all abstract shapes and textures, and as Marty gets his bearings, so does the viewer.”

Although Kutchins had established the warm contrasty look of scenes in Mexico in previous episodes, the introduction of Marty’s dungeon-like hole that opens Episode 4, became an interesting challenge for Salas. As he continues: “I created a neutral/ cool look for when the room was darkened, and then warm incandescent flood lamps for the torture lights [Byrde is subjected to sleep deprivation and incessant loud music]. I tested different lights with David [Bomba] and ended up having our electricians swap out for lower wattage halogens, and then added a streak filter to enhance and distort the lights when they kick on. “We wanted viewers to feel Marty was having his eyes blown out without having it be actually hard on the eyes of those watching the show.”

The VENICE and Leica lens package dynamically alter Ozark’s visual landscape in Season 3. But those weren’t even, perhaps, the biggest changes to the look of the series. Before Season 2, Netflix changed its release delivery to require Dolby Vision, with new home displays now mostly being HDR-equipped, and even tablets and other smaller display devices becoming HDR compliant. That meant the show had to be versioned (mastered) in HDR, with many legacy [SDR] viewers seeing the end product in HDR generated by a computational analysis within the Dolby Vision process.

Salas had gone on to shoot another Netflix show, Raising Dion, and immediately implemented an HDR workflow to view both HDR and SDR simultaneously on set. When it came time to prep Season 3 of Ozark, Salas tweaked his Raising Dion workflow for Ozark. He and Kutchins flew to Atlanta for a camera and workflow test, and, based on that, Stipan created their HDR LUT for on-set viewing.

“I made a global trim that matched the HDR as close as I could get,” Stipan recounts, “and then I went through the SDR episode to make sure it looked as good as it could be, and nothing bumped me in terms of highlights and shadows.”

Kutchins and Salas were then able to check both SDR and HDR versions whenever they were dealing with high-contrast situations, i.e., windows, backings, and practicals on set. Their digital imaging cart consisted of two Canon V2411 HDR monitors fed by an AJA FS-HDR rack, which held the show LUT’s and simultaneously fed an SDR version downstream to Video Village, which approximated the Dolby Vision down-convert.

“[Being able to look at both versions simultaneously] informs how you expose faces, especially on a show like Ozark, which lives in the shadows,” Salas concludes. “We could all make those decisions in our delivery format versus having to deal with it later. To use an analogy: it would be as if we were shooting a color show, and the monitors on set were all black and white. Now, we could have a good idea of what the transform is going to be and could make a judgment based on that, or we could just be viewing it in color instead of in black and white. It really is that extreme of a difference when it comes to a show that is finishing in HDR or SDR. This new workflow got us a lot closer to seeing what we were going to eventually be grading in the DI suite.”

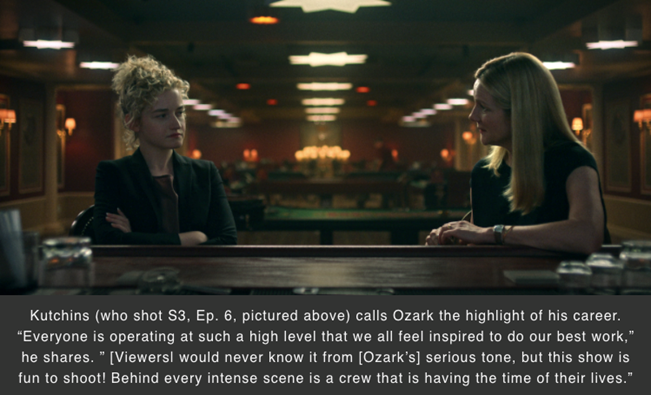

Semanoff, who describes Ozark as the “highlight” of his career, says he has been “spoiled for life” by Jason Bateman’s trust and partnership. “Over the several productions Jason has brought me onto, he’s always treated me like a collaborator,” Semanoff says. “On Ozark, in particular, he has encouraged me to help set and maintain an aesthetic for the way the camera moves, or doesn’t move. Beyond which he entrusted me with directing two episodes, which is a special experience. Besides the amazing cast and crew, [Bateman] and [Chris] Mundy encourage directors to approach their episode[s] with a freedom more indicative of a feature film. It’s liberating!”

For his part, Kutchins says he’s “so pleased” the dark drama has found such a huge audience. “My Ozark experience simply wouldn’t be the same without the amazing team of people who came together to make the show,” Kutchins concludes. “Everyone is operating at such a high level that we all feel inspired to do our best work. [Viewers| would never know it from [Ozark’s] serious tone, but this show is fun to shoot! Behind every intense scene is a crew that is having the time of their lives.”

“With Season 3,” Salas finishes, “the canvas and scope [of the series] became larger, while simultaneously delving deeper into these intimate character studies of our anti-heroes. The combination of a larger sensor, extremely limited depth of field, when appropriate, and expanded color and tonal range combined to enhance the visual language of Ozark without straying too far from the familiar look.”

Ozark (Season Three)

Directors of Photography: Ben Kutchins, Armando Salas

A-Camera Operator: Ben Semanoff, SOC

A-Camera 1st AC: Liam Sinnott

A-Camera 2nd AC: Kate Roberson

B-Camera Operators: Greg Faysash, SOC, Christopher Glasgow, SOC

B-Camera 1st AC: Cristian Trova

B-Camera 2nd AC: Johnny “Utah” Hoffler

Digital Loader: Taylor Seaman

Digital Utility: Walker Markey

Still Photographers: Steve Dietl, Guy D’Alema, Jessica Miglio, SMPSP, Tina Rowden