by Mario Oliva, Mario Oliva

Christopher LaVasseur works as cinematographer in this American TV series based on the comic book character Warrior Nun Areala by Ben Dunn. It tells the story of a woman brought back to life by the halo. Ava, tetraplegic and abused, died in an orphanage but, thanks to the halo, is able to see spirits and demons that float among us undetected. Even if Christopher designed the visual style, he shares the cinematography of the series with Spanish cinematographer Imanol Nabea.

Christopher LaVasseur is a cinematographer, and a person, that will not leave you indifferent. As he says, enthusiasm is contagious and addictive, and he is the embodied proof of it. Chris works on an energy frequency high above most of the people and he brings his collaborators up to that level. No matter what he is doing, but the creative process in which he involves everyone around him promise to be different to anything you have seen before, almost a transforming experience.

Mario Oliva: Could you please introduce yourself? How did you start in this business?

Chris LaVasseur: I started in the business through the camera department, so when I first got out from college long time ago I applied for jobs at camera rental houses and I got one. At the facility where I used to work, I got to meet camera assistants and I started to network with them. I got to know the cameras that were out at the time and I cleaned too a lot of cases.

I was offered two jobs when I was at the camera rental house. One was as a film loader on a job called Single white female. It was directed by Barbet Schroeder and Luciano Tovoli, which is the cinematographer of Suspiria, the original one in 1977 with Dario Argento, so I was like: ¡I really want to work with this guy!

I also got an offer to work in Malcom X as a film loader. Actually I became second assistant camera on B camera on that film. From there I started my way up and eventually, in 2009, I became a full time DP.

I made it a point to ask other crew members what were the jobs they were working on. And if they were working with DPs I could learn from, I would ask if I could just go to watch how they work. I wanted to learn from academy-awards DPs and I kept doing that. I used to just sit there and kind of shadowed these guys, just watching them doing their craft.

So you had clear in your mind from the beginning that your final goal was to become a DP?

I picked the camera as my path in Brooklyn College, where I did the major on cinematography, media and television. You learn film theory there. I am not saying that was not interesting, but my real film school was what I got by working. There is so much more that you got to learn when you are on set, like how to manage your crew, how to delegate, how to talk to the gaffer or to the director. You learn that growing up, and I found very valuable to do it through the camera department. Growing into the steps, doing the apprenticeship. I feel personally that for me was really important to do it this way to become a full rounded cinematographer and to be the best I can be.

While you were climbing up the camera department ladder were you doing any jobs or projects as a DP?

Any time, even when I was a focus puller, I was taking advantage of any time to draw lighting diagrams on set of what the DP was doing, I was like a sponge. The first feature film I shot was a 60.000$ film on super 16mm. I did not care; whatever it was I would shoot it. And there was no money, I would do it for free. The more I did, the better I would be. That was my film school, just to keep on shooting

As I understand you are part of Innovative Artists agency. How did you end up belonging to this collective? Did it change your way of getting jobs? What means for your career working with them?

The agency where I was retired and gave all its roster to Innovative Artists. Innovative Artists absorbed all the DPs from the previous agency. There were unusual circumstances, we went through a kind of trial period for both. And it was successful, they are a wonderful team; I feel they are like my family.

What happens in the film industry is that you are as good as your last job, that is your reputation. Many times I get jobs through producers that have heard about me. For Warrior Nun, I was working with a director and she got to do the pilot for the TV Series. So, there is a variety of ways of getting a job.

Had you worked before with any other of the directors working in Warrior Nun?

Actually I had not worked before with any crew member of the project before, except for that director, Jet Wilkinson. We had that familiarity in the project. We knew what each other needed. I knew how to help her out, and she did too. So it was like a back and forth thing. We had this kind of quick short hand when communicating between us. But I still had to go through the process of being accepted by the showrunner, Simon Barry, and by Netflix too.

How was your creative relationship with the directors? Did they get involved in the visual aspect of the project or they used to give you more freedom? How did you deal with changing directors so often? Did it affect your way of working?

That is another thing that you do not get to know at film school. As a cinematographer, when you go from director to director everything changes. Some of them give you all the freedom, some directors have a strong vision, and others try to establish a more collaborative way of working. Normally it ends up into a great collaboration, back and forth. And with the directors that know exactly what they want, I try to find some room to be creative and to contribute.

You have to be like a chameleon with them, to adapt yourself to their different personalities. That is what I love about the process, that it is never the same. I love using movies and art as references. I am always bringing in paintings, especially for Warrior Nun, where we had flashbacks, so we could get much more classic. References just get the ball rolling, get us into a conversation. But the next director may be a little bit different, so the conversations will always change, and that is why I like it. I enjoy being adaptable and changing with them.

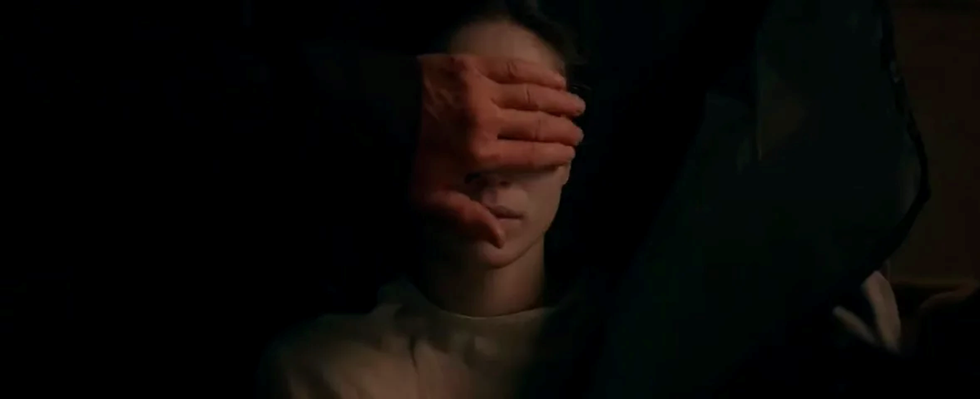

Chris while shooting Warrior Nun

How was the first contact with them? Did you have enough preproduction time?

In Warrior Nun I was rotating with a very talented cinematographer, Imanol Nabea. While I was in preparation Imanol was shooting, and vice versa. I took advantage of that time to get slowly into the director’s head, to learn their taste, their aesthetics and what they liked. By the time we had to start to shoot we already knew each other. Because when you are on set it is like a running train, you do not have much time to discuss. All the conversations must have been done in preparation. But during preproduction we have lunch together, we have dinner, we are always talking about different scenes, different tools to use and different ways of telling the story.

I had conversations as well with the production designer, Barbara Perez-Solero, and the costume designer, Cristina Sopeña. So we were all talking together to create the look and the feeling of the show. There were always bouncing ideas between each other, it is an amazing process. I never get tired of it. It is a very beautiful way of searching and it is never the same, every location, every scene and situation it is always different.

Coming back to the references you say you were using. Were there references for the whole project or they were changing from one episode to another?

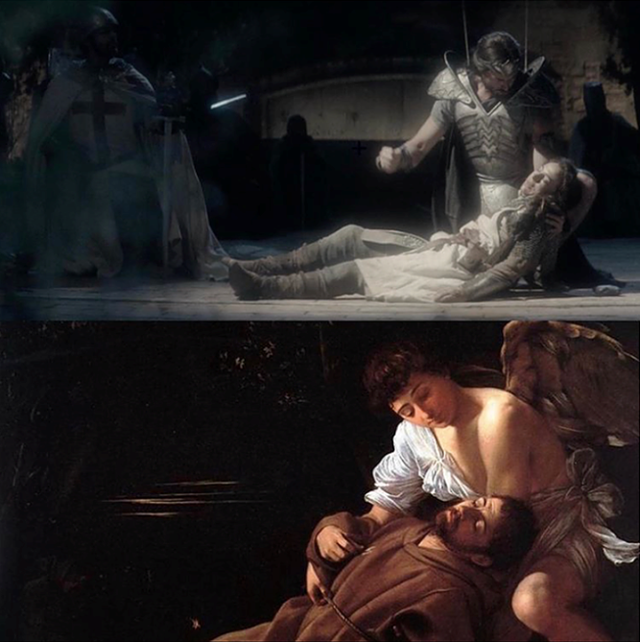

We had like a moodboard for the look of the project to show to new directors the main inspirations we were using. Some of them were Caravaggio and Rembrandt paintings. I was always bringing in those paintings because there were many candle lighted scenes. In episode number ten we had this flashback for what I literally stole the aesthetic from Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, from Caravaggio.

We tried to keep some consistency regarding the mood. Before a new director came to the show, Simon used to talk to them to explain the style of shots we were doing. We were always using, for example, wide angles close ups for a graphic vibe. There was a common visual theme throughout the whole show.

We avoided conventional coverage of the scenes. We were not getting more coverage than what was needed. When using a 25mm lens two feet away from somebody it is difficult to put another camera in. We were going for a very graphic frame and composition.

Flashback scene from Warrior Nun and the visual reference from Caravaggio.

Were you able then to use the two cameras you had most of the time?

It depended on the scene, how it had been blocked and how we want to photograph it. Let say we played with B camera almost half of the time. But there were action sequences in which we had like three or four cameras at the time. I would always make sure that the first shot that we would compose was the one that A camera was doing, because that was the right place to put the camera.

I think that is a great way of working because you have the flexibility of adding a second camera to a one camera project. It is like that is not a must to get a profit of the second camera all the time.

Here is the thing, and I am a big believer of it. In some shows they tell you to put a second camera even if you are not going to get a good shot. The second camera is sometimes doing a shot that the DP is not even aware of what is doing. So I wonder what story is telling that camera. To me, there is a place to put the camera to tell the story visually, a place where the camera needs to be. I am not saying that I am always right. Sometimes I build the frame for the A camera and it is a great shot, but then I see what the B camera is doing and it is even a better shot. In Warrior Nun it happened actually several times. I rely on my camera operators, on the grips, the gaffer… And when we are on set I welcome their input.

Coming back to that graphic style you were talking about. Was there any element that you consider fundamental to keep the coherence of the photography you were making on this project? Could you explain in general terms what was your visual proposal for the project?

We went for that wide angle graphic style. We tried as well to keep the camera angle just subtly below the eye line, a bit lower. So we would give people more power on the frame. In Warrior Nun there are a lot of references of God and religion. So there is as well this point of view of God from high above, wide angle shots looking down to people like God is looking down on them.

We always talked about having these extreme shots. We would cut from this very wide angle shot to a very tight close up to make you feel the cut, the edit. We wanted to unravel the composition rules to go to these extremes. Like using negative space, putting someone all the way on the right of the frame to leave all the left side of the frame completely empty to make you feel the space.

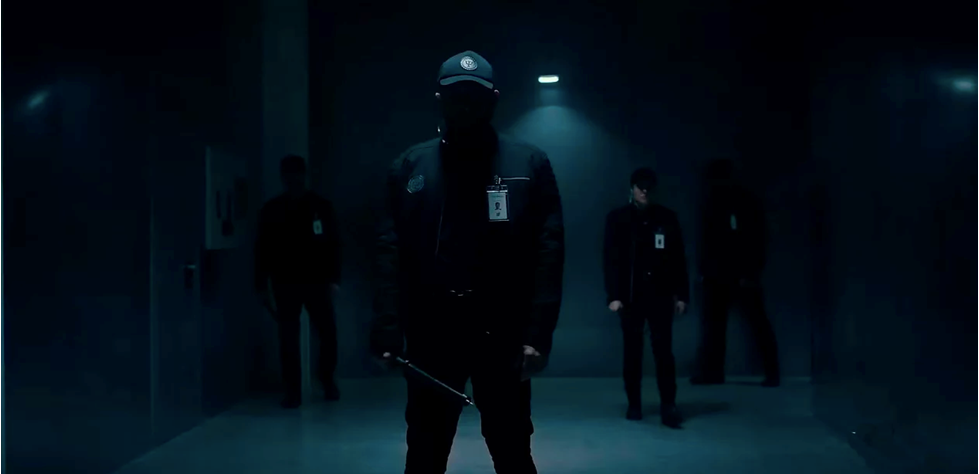

About the lighting, the two key atmospheres that the viewer will notice are the church where they live, the Warrior Nun world, and then, the art-tech world. The Warrior Nun world is warmer, often lighted with candle lights. Even during day time exterior we were keeping it warm. But when we go to the art-tech world everything looks clinical and metallic. It is very cold and geometrical. The lines are vertical and horizontal, the look is very scientific. The colours tend to be colder. Warrior Nun world is dealing with religion and faith, a higher power. While the art-tech world is dealing with science and a more practical approach. So there were two worlds treated very distinctively.

The two key atmospheres are the Warrior Nun world and the art-tech world

It sounds like you were using all the power and the tools that the cinematography offers to you.

Not only the cinematography, but we were using as well costumes, the production design… to reach a goal. If I was doing the lighting I like, but I was not in the same page with the production designer and the costume designer, it would be useless. We were using everything at our disposal to tell the story. We were always collaborating, I would contribute with the lighting, lenses, colour, contrast… I had to be careful not to go too dark because it would compromise the costumes. For example, when Cristina was using black costumes we would try to make them have some shimmering on it because we were lighting so dark that they just would disappear into the background. So having these conversations with other people of the crew is really important.

It is great because that makes that everyone's job is appreciated and relevant.

If something in camera does not look good it is very hard to make it look better just with lighting. Most of my job was done by these two women that were making beautiful locations and great costumes. So you put the camera and then you light it and it becomes a trilogy of collaboration. It makes my job much easier, to be honest.

It happened sometimes to me in another projects that someone wanted a dramatic look on a white room. It is very hard to work alone, if you do not have the look in mind from the beginning, our job is more difficult. I remember a DP I worked with saying: If you fight a location, maybe it is not the right location. But I never had that problem in Warrior Nun. Every location I went to, every costume, everything about the acting, the directing… It was a very beautiful time for me. It is one of the favourite jobs I have done, such a rewarding project to work on.

What about the texture? Were you using any in-camera filtration?

We chose the Sony Venice, suggested by Imanol, with the Cooke S4, which have a very beautiful rounded softer edges. Imanol and I agreed on that we wanted to avoid that sharp look that is so popular these days. Everyone now like this diamond super sharp lenses. I like it softer, I wanted to take the edge off to be more cinematic. In film is not that sharp. So we used 1/8 Black Pro Mist in-camera filtration for the whole show. If we were doing a close up and we wanted an extra more softening, we would put ¼ Black Pro Mist instead. And the other effect that we were looking after was that blur that this filter gives to the candle lights, that soft glow that is more similar to what our eyes see than a sharp flame.

We used specific filtration per episodes, per director and per location. The Warrior Nun world happens all over the time, you have present time while they are working at the church, but then we had this sequence in episode 5 and 6 in which they go to Africa. For that sequence I used tobacco filter to give that brownish look to the images, just to separate it from Spain. To give it a different vibe.

And for the flashbacks I did with Simon we used heavy filtration. I think we put a full White Pro Mist to give it that blooming quality. One of the main films we used as a reference with Simon was Excalibur, the John Boorman film in 1981, shot by Alex Thomson. Simon wanted the look different, so we shot with anamorphic lenses. We change the filtration, the lenses and even the aspect ratio for the flashbacks. We used the old 2.35:1 anamorphic aspect ratio. We were trying to give a Lawrence of Arabia feeling to it.

Excalibur trailer, one of the main references for the project

What other film references did you have for the show?

We looked as I said to Excalibur, Lawrence of Arabia, Gladiator. We checked Gladiator especially for this scene in which Ariala jump off the horse and starts battling with her enemies. We took as a reference the battle scenes from the beginning of Gladiator. I love the coldness against the warmth of the fire. I suggested to Simon to have fire in some places so we could create that colour contrast. Apart from that, Excalibur was the biggest influence for me.

It is interesting that all the film references you are talking about have an epic vibe.

We were not trying to take lemons to make lemonade, we were trying to make dimes look into dollars. Simon and all the directors that came in were very ambitious and we welcomed it. We wanted to make their ideas possible. It is a team effort and everybody put their resources together. To me, the money never got in the way. If I needed these lights we did not have, I would go to talk to the gaffer and we just started working it out. But the great thing is that everyone was on board, from top to bottom, from the showrunner down to the PA. You need those wheels on the car. If you think that you can do it on your own, you are only going to hurt yourself. You do not need big resources but the way to do it.

Another great quote is: You will find you are limitless in limitations. You have limitations, you have compromises, but then you become limitless, you get more creative. If you have everything at your disposal, you are not going to think about being creative, because you have every tool. But even if you are missing a tool, you need to make it work anyway. You have to tell the story, so then you start thinking about how to do it. And someone else put their mind into it, then someone else says something, and suddenly you have this pull of creativity and you come up with an idea that you would never think of if you had all the tools at your disposal.

"We were trying to make dimes look into dollars."

The less you have, the more creative you have to get I guess. Talking about the workflow now and your relationship with the DIT. Did you design LUTs in preproduction?

Rodrigo Gomez, an artist himself, was the DIT. He was my right hand and my comfort zone, one of my main collaborators, as important as Cristina and Barbara. We had a location like underground catacombs under the Vatican. We lighted it with candles, we did some test with the Warrior Nun world costumes to create a LUT for the show. This one LUT went through the whole show.

However, while going through different locations, we were doing CDL, Colour Decisions List, which are like adjustments in terms of colour and contrast. We have the LUT and the CDL goes on top of it. So we had the LUT as a basis, like a film stock, but during the shooting we were doing those smaller corrections. So there was this consistency the whole time, but there was also a free flow, we were always evolving.

How was the communication between what you were doing on set and what happens after that in postproduction? Were they using your references for the grading?

The grading took place in Vancouver. Because the production company was from there. I wish I was available for the grading but I was into another job. And this happens very often. The best thing would have been to go to Vancouver and sit down for a week to set up the colour correction process. But I had to do it remotely.

Rodrigo was taken stills during the shooting as rough references. We used those references to show the production how we wanted the look. I sent those to the colourist and he sent back to me stills with three different options. Then we started talking, and I involved Rodrigo too in this process by sending him the stills from the colourist. So again, we three were joining forces to create the best image. I really enjoyed this process and this is why I think it looks special.

I think is very interesting that inclusive philosophy and to trust and listen to everyone around you.

If you are shooting a show and you are like a horse with blinders on, you only have your vision. There are times when something is very special and magical, but you are just focused on yourself. It should be an open discussion.

"The great thing was that everyone was on board"

What would be your ideal project in the near future?

It does not matter the genre, but the people involved have to be passionate about the story you are telling. Enthusiasm is infectious, everyone gets hook up. The visual medium is always much more powerful than any other language. And If the people I work with understand that, I am in.

I am not only showing references for lighting, I show references for the shot structure, for editing. You have to know how shots are cut together. You need that knowledge as a cinematographer to create meaning, because at the end everything goes around how you visually tell the story.

You read the script and you understand how a character goes through a journey, but you need to develop a visual story that evolves along the journey. If you shoot it conventionally you are just providing a service, your work is as if you were assembling a car, it is mechanical. You have to discern the subtext, to know what is going on, what is the underlying story. That is what is fascinating to me.

People watch the projects I have work on and they think I love action scenes. But sometimes two people sitting at a table talking to each other have a massive underlying subtext going on. I am more interested on that than in any action sequence. Two people just talking can be very powerful. It is not specific where the intensity comes from. It can come from anywhere, but you have to be aware of what is going on to be able to express it.

Sometimes you are stuck until you see the rehearsal, and then you see, for example, something in one actor that unravels the creativity, and that gives sense to the work you are going to do or, at least, it is useful to start a conversation about it.

If you have done all your homework before shooting, then you are going to be able to find one of these magical moments. You are ready to take advantage of the opportunities that come up and to move the show to the next level. They are happy accidents and you have to be there to experience it. I cannot describe it, but you have to try to keep talking about this magic, to have conversations and to get everyone involve in the process. You want to get better, you do not want to get comfortable, because if you are just going to do your job ¿Why are you waking up in the morning? It is a strive to get better, to be a better person, to smile every day. I did not come there just to get it done, I came to kick ass.

"The visual medium is always much more powerful tan any other language."