IT TAKES TWO DP’S (WHO ARE BOTH PAST GUILD ECA HONOREES) TO HARNESS THE LEADING-EDGE LIGHTING SCHEMES THAT POWER BLACK LIGHTNING.

ICG Magazine--By Pauline Rogers, Photos By Richard Ducree & Bob Mahoney

Nine years ago, Garfield High School Principal Jefferson Pierce retired from his superhero persona, Black Lightning, after seeing the effects it had on his family. However, when Pierce’s hometown of Freeland goes under siege from a local gang called the 100, there’s no other choice for Pierce than to become the electrified crime-fighter his namesake powers fire off.

DC Comics’ first African-American superhero – created by writer Tony Isabella and artist Trevor von Eeden – was developed for the small screen by the husband/wife writing/directing/producing team Salim Akil and Mara Brock Akil (Sparkle, Being Mary Jane, The Game, Girlfriends) with the help of TV superhero producer Greg Berlanti (Arrow, The Flash, Supergirl, Legends of Tomorrow). To visualize the show’s unique look, the Akils hired Emerging Cinematographer Awards honoree Scott Peck to set the tone with the pilot and continue the series, alternating with fellow ECA honoree Eduardo Mayén. In the early discussions with Salim Akil, who directed the pilot, and Producer/Director Oz Scott, one of the ideas frequently voiced was, “Of a comic book, but not a comic book,” meaning the show should have comic-book elements but look gritty and real. And throughout the show’s first season, both Peck and Mayen have referred to images from DC Comics as springboards for color and composition.

Camera movement has been key for both shooters. Peck says “to visualize the Black Lightning universe, we needed to use all the tools available. Whether that’s dolly or crane, we try to give the camera just a little float so it doesn’t get too static. A-camera/ Steadicam operator Brian Nordheim and B-camera operator Bob Newcomb [SOC] do an amazing job of blending that technique, so it feels almost imperceptible.”

For both operators, each episode offers a stylish, feature-like scope. “It pushes the boundaries of the episodic form,” Newcomb shares. “Our DP’s encourage us to look for new and different opportunities in composition and framing.”

Nordheim agrees, citing a scene for a planned 50-foot Technocrane straight down a city street in Atlanta. “It’s where Black Lightning comes walking up into our 14mm lens and we have to boom up over the top of him to eye level,” Nordheim explains. “He then turns toward a high-rise building, and we had to come back down his body and look straight up behind him to the very top of the building – 90 degrees. We paused, and then I had to tilt back down and follow him into the front doors of the building, down some stairs and into a fight scene, which transitions into a stairwell, where we switched camera modes to handheld for the fight.”

But in fact, Nordheim says they had to abort the crane and do it with Steadicam, “because we could not tilt 90 degrees without seeing the head of the crane,” he continues. “We always have tools like a large crane available, but making creative choices to benefit the shot – and continue that feature quality – is important to the show and the schedule.”

That “float feeling” Peck describes is not without its challenges for Black Lightning’s focus pullers, who frequently must contend with wide-open shots through foreground elements.

“Often, during fight sequences that involve Black Lightning,” describes B-camera assistant Alan Newcomb, “the light is flashing or undulating from the electrical interference he causes. Combine that with darkness and wide-open lenses, and you sometimes abandon both the monitor and any technical methods of pulling focus in the moment – you just need to feel them coming at you and hope that when the lights come back on you are still good!”

For A-camera AC Anthony Zibelli, one interesting challenge came on the pilot – where Pierce’s two daughters (who also have super powers) were coming down the stairs with Anissa yelling at Jennifer for going to Club 100. “Steadicam – 50mm wide open at a T1.3,” Zibelli recalls. “We had to follow the dialogue with some shifts to cell phones and reactions of actors that weren’t talking and back to dialogue. It was difficult, but nailing it was a great feeling.”

Also unique to the series are Black Lightning’s physical attributes. As Zibelli explains: “Although he may be talking, you need to focus on his hand, knowing it is glowing with electricity, which they put in with CGI. But then knowing when to go back to his dialogue before the scene is over and you reach the important part of his speech. Then there are his goggles – where you have to remember to focus on his eyes, not his goggles. You can tell the difference, which is in focus at a T1.3. And it always should be his eyes.”

“In this world,” Peck elaborates, “every time we see Black Lightning, he directly affects the energy and lighting around him. As the electricity begins to fluctuate, lights flicker, spark, and even sometimes explode. We knew we needed to come up with an unconventional approach that not only gave us maximum control and flexibility but that was also efficient and affordable.”

Showrunner Salim Akil and DP Scott Peck

Peck, Mayen and gaffer Joshua Stern sat down for a series of conversations that ultimately led to the team eliminating tungsten lighting from their package. Set lights consist of LED units from ARRI, Digital Sputnik, GroundedLED, Litegear, and Quasar Science, with the goal being to balance the comic book palette and still achieve flattering colors for the cast’s skin tones

“We use lime green through indigo blue on the cooler side of things, and peach through chocolate on the warmer side,” explains Stern. “In addition to LED’s, we use intelligent theatrical lights and wireless controls. Our set has to be quiet, fast, and cool, so conventional tools just don’t fit our needs. A light comes in, gets placed, the control number is called out, and we are off to the races – color, intensity, and even focus are often just a click away.”

Which makes for an interesting mix. Episode 109 features a large scene in the Greenlight factory, where Black Lightning and Anissa (aka “Thunder”) attack the facility responsible for making drugs in the city. They used all their lighting tricks, throughout multiple floors of an old water treatment plant in town. “More than a hundred lighting instruments and practical fixtures,” recounts Stern. “Both of the superhero suits, multiple handheld LED gun flash panels, and a large number of fire effects and explosion cues.”

Stern adds that having one location function as six different locations over two days was a real test. “When utilizing the amount of tech that we do,” he continues, “you have to take into account the materials a building was made with and its proximity to cell towers and other wireless interferences – we aren’t just running heavy cable and using classic tools.”

Big sets on BLACK LIGHTNING are often cross-boarded across episodes, so Mayen and Peck need to be in relative sync. Take Episode 109 (shot by Peck), which sets up Episode 110, which takes place in a warehouse. “Scott wanted to do overhead lighting,” Mayen recalls. “I wanted practical lighting for the control. We both knew this was going to be handheld.”

The space offered high bay metal halide lights and no windows – a secret storage room where Black Lightning and Thunder fight the bad guys. Mayen and Stern realized they would have to control the flicker while shooting at high frame rates and recording dialogue.

“With only two days of prep to rig and light, turning off the flickering overheads was the only way to go,” Stern states. “Eduardo had us dress in 120 four-foot Quasar Science Crossface tubes on the front and back of all 60 columns in the space, set them at 6000K, giving the space a really beautiful steel blue look, while maintaining a rich fall-off in the shadows.” The moving parts within the story (set) were also dressed in Quasar tubes and diffused with active diffusion to change the opacity of the glass as the actors moved.

Black Lightning also offers the DP’s the chance to work in unusual smaller setups. A favorite of Mayen’s was something he took directly from a comic book – the “Blam!” shot.

“I remembered the original Batman TV show, and the ‘BLAM’ punches,” he recalls. “So, I thought, what if we could get something that is iconic for our show – with a twist?”

The solution was to put a Micro 4/3 Black Magic camera with an 8mm lens on the forearm of Black Lighting’s suit – and punch-in. The result was a cool fist in the foreground as he hits someone in the face!

As for the other star of the show – Black Lightning’s suit – Peck built a small set in pre-production and tested the outfit, finding it an excellent reflector of light. The chest plate is made up of blue and gold LED lightning bolts that have the ability to dim up and down. “The light intensity displays how much power he has,” explains Peck.

“When the lights are dim, he is out of juice! Black Lightning needs to draw power from the world around him, otherwise he can run out of energy.”

To properly light the suit, the Black Lightning team often has to eschew elaborate location lighting for elements they can more easily control. Mayen and Peck work with Stern and Console Programmer Jason Clairy to dial-in the intensity of the suit and its potential effects – using Theatre Wireless RC4 dimmers and small battery packs to make them as “nimble” as possible.

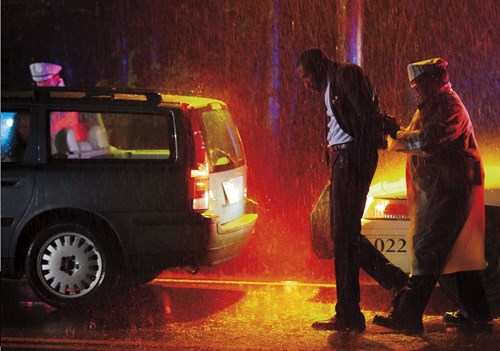

The fight scenes at Club 100 from the pilot are a prime example. Pierce goes to rescue his daughter, Jennifer. But needing to protect his identity, he opts to draw energy from “the grid” and shut off all power inside the club – his enemies can no longer see him. “Our first step was to set our ‘movie blackout’ as a base,” Peck remembers.

They then set the intensity of the flicker as he pulled power, and augmented the scene with custom remote-controlled LED hand pads that were set to a steel-green color. Clairy would cue the “lightning bolts” based on action points.

Such challenging setups are aided by the presence of on-set visual effects supervisor Kimberly Rasser. “It’s about being involved in the creation of ideas from the beginning,” she relates. “In prep for this sequence, for example, Josh, [Scott Peck] and I talked about interactive lights attached to Black Lightning’s hands. These practical lights would add a more dynamic feel to the fight, especially in the dark lighting. It proved effective in making Black Lightning’s powers paramount in the scene, and it set up a perfect integration of VFX elements in post.”

That’s when Encore’s Armen Kevorkian, senior visual effects supervisor/creative director, gets involved. “Once a sequence is cut,” he relates, “we spot the VFX and pull dailies, ingest the footage and set up everything – track and lay out, FX simulations, lighting and rendering, compositing. I work closely with the artists to come up with the final look, which is eventually what the audience sees on TV.”

Another big asset is having on-set DIT Justin Warren, who built his system exclusively for the series using an Echo 36 and a Chuck May mount system. “It’s an unusual arrangement of setting the DP/DIT monitors in the front [two 24-inch Flanders OLED’s] and the director/script village on the side,” Warren describes. “It’s great having the DP and director so close, and it’s obviously great for me to be so close to script – I can constantly keep track of where we are for my color grades. There’re a lot of action and stunts on this show – so it moves fast.”

Warren calls Black Lightning a “vibrant and exuberant show. From an artistic point, it’s not a typical CW show,” he states. “It’s grittier, and darker, but still colorful. There are many visual themes that go with either characters or locations.

“So many times, when we shoot offspeed,” Warren continues, “where every single light is dimming rapidly up and down [when Black Lightning steps into frame and ‘disrupts’ the power], having someone strictly technical behind the monitor to help dial-in a specific shutter angle to avoid flicker is critical. There is no time to test. We just have to get it right.”

For Peck and Mayen, Black Lightning is a very ambitious show loaded with complex and creative challenges. “We’re doing large-scale action and VFX sequences on a television budget and schedule shot over the course of eight days,” Peck concludes. “There is no margin for error. That wouldn’t be possible without the full support of this great team.”

LOCAL 600 CREW

Directors of Photography

Scott Peck

Eduardo Mayen

A-Camera Operator/Steadicam

Brian Nordheim

A-Camera 1st AC

Anthony Zibelli

A-Camera 2nd AC

Alfredo Santiago

B-Camera Operator

Robert Newcomb, SOC

B-Camera 1st AC

Alan Newcomb B-Camera

2nd AC

Zsolt Haraszti

DIT

Justin Warren

Still Photographers

Richard DuCree

Bob Mahoney