by: Owen Gleiberman, Variety

We’ve never been too crazy about the phrase “embarrassment of riches.” Why the embarrassment? Can you really have too much of a good thing? When it comes to documentaries, we think you can’t, so we prefer to categorize the best documentaries of 2021 as a pride of riches. We included 20 on this list because we didn’t feel, in our right minds, that we could do without any of them. And the range of movies here is a testament to the vast spectrum of work now being done in the non-fiction arena. A number of the films we chose are music docs, but that’s simply because there was so much extraordinary, impossible-to-ignore work in that area. Yet the movies on this roster also encompass subjects like race, politics, art, food, the police, the animal kingdom, the environmental crisis, the opioid crisis, and a rescue mission more gripping than any thriller. To anyone who doubts that docs rule, our response is simple: get real.

Ascension

No matter what your image of modern China, it’s nowhere near complete until you’ve seen it through New York-based, China-observing director Jessica Kingdon’s eyes. Working in the mold of photographers Lauren Greenfield (“The Queen of Versailles”) and Edward Burtynsky (“Manufactured Landscapes”), the Tribeca Film Festival winner trains her camera on the impacts of China’s fast-exploding economy, leaving audiences with striking and frequently absurd scenes burned into their imaginations. Kingdon’s curiosity spans the class divide, from assembly lines where women prepare silicone sex dolls for demanding clients to private dining rooms where butler-attended elites learn how to eat a banana with fork and knife. Without contextualizing what we’re seeing, the hi-def collage asks us to make sense of a society even more stratified and excessive than our own. —Peter Debruge

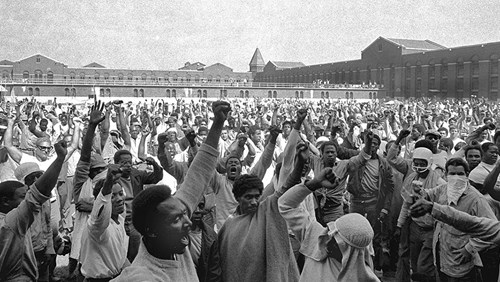

Attica

The events that took place at the fortress-like Attica Correctional Facility in September 1971 remain shrouded, for too many, in a murky mythology. For 50 years, the cataclysm has been called an “uprising,” a “riot,” and a “massacre,” when in truth it was all three, as well as a lunge for human justice. Stanley Nelson’s monumental film (codirected by Traci Curry) is nothing less than a definitive record of what took place, and why it still vibrates in the air of our national consciousness about race. Nelson, utilizing never-before-soon archival footage, takes us right inside the prison, letting us share the flickering hopes of inmates who demanded improvements to their egregiously degraded conditions. We witness the thorniness of the negotiations, the power struggle that was playing out underneath it all, and, finally, the staggering crime that was committed: a slaughter sanctioned by a government willing to murder everyone on sight — prisoners and guards — to prove itself invulnerable. As you watch “Attica,” both the hope and the tragedy live on. —Owen Gleiberman

The Beatles: Get Back

Only a month after it was first shown, Peter Jackson’s eight-hour chronicle of the three weeks in January 1969 during which the Beatles rehearsed and recorded what would become “Let It Be” is already a documentary you can’t imagine being without. It’s casually observant enough to capture who John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr really were — how they hung out and argued and joked around and made music and talked about the old days as if those days had never gone. Jackson, who brilliantly assembled the footage, whittling it into a kind of anecdotal verité novel, has also caught how much the Beatles loved each other — even though they fought, at times, the way only brothers can. The Beatles remain the most larger-than-life of all pop stars, but after watching “Get Back” you almost feel like they’re your friends. —OG

Becoming Cousteau

Director Liz Garbus enticingly captures the story of how Jacques Cousteau all but singlehandedly spearheaded the exploration of life under the sea — a quest that, at the time, felt as mysterious and unprecedented as our voyages into space. To accomplish what he did, not only exploring “the silent world” but bringing it to all of us, Cousteau had to be an athlete, an inventor, a film director, a scientist, a daredevil, and a just-posed-enough-in-his-red-watch-cap-to-look-unposed media personality. Where “Becoming Cousteau” takes the viewer into vitally current terrain is in shedding new light on Cousteau’s perception that he was discovering not just the beauty of the sea, but the decay of it — the early warning signs of environmental collapse that he saw before just about anyone, and spent the rest of his life bringing to the world’s attention. —OG

A Cop Movie

It says a lot about Alonso Ruizpalacios’ dizzyingly meta exploration of performance and appearance within Mexico City’s notoriously compromised police force that we’re not wholly sure it actually is a documentary. It is, however, one of the most original, inventive, and fascinatingly constructed films of the year. It follows two Mexico City cops through onion-layers of mockumentary, docu-fiction, and then finally into a behind-the-camera filmmaking exposé, and what’s most surprising is that despite all the mischief — the lip-syncing, actor fake-outs, and fourth-wall hijinks — it yields sober insights into the insidious way the “role” a police officer plays can affect the cycle of police violence breeding more violence, which exists far beyond Mexico’s borders. —Jessica Kiang

The Crime of the Century

Some conspiracies are true, like the one documented, with sobering evidence, in Alex Gibney’s masterful muckraking exposé: a four-hour investigation into how the opioid crisis unfolded in America. The film documents how Purdue Pharma, starting in 1996, brought OxyContin onto the market and literally pushed it, dumping insane amounts of the semi-synthetic painkiller into small communities in a way that was morally (and maybe legally) indistinguishable from back-alley drug dealing. Across the country, doctors and pharmacies sold it like candy, as the regulatory agencies looked the other way. And by the time Insys Therapeutics introduced fentanyl in spray form, paying off dozens of congressmen to rewrite the laws, the “crisis,” rather than getting solved, had only entered a new realm of disaster (where it, in fact, remains). “The Crime of the Century” is an essential portrait of an America ravaged by the despair of addiction, and by a corporate medical structure that embraced, at every turn, the corruption of legalized drug pushing. —OG

Gunda

It’s like “Charlotte’s Web” done as a wordless piece of direct cinema shot by Ansel Adams. Viktor Kossakovsky’s serenely observant and transporting nature doc is so devoted to the reality of being an animal that it doesn’t have to pretend to turn animals into “us.” Rather, it slows us down to the animals’ rhythms, so that we start to connect to the emotional vibrance of their existence. The film follows the daily life of a sow named Gunda and her close to a dozen piglets, who she sniffs, nurses, herds, referees, and then, quite movingly, loses to the outside world. There are also detours into the lives of a stately herd of cows and a one-legged rooster who stalks through a garden as if it were a primeval forest. The extraordinary sound design makes it feel like every rustle of leaves, and every pig grunt, is part of the cosmic sphere. —OG

Listening to Kenny G

Flooded as we are with fan-service music docs, it’s refreshing to find one that dares to question the merits of the icon it depicts. Global sax symbol (and top-selling instrumental artist) Kenny Gorelick plays along with director Penny Lane’s unconventional approach, sharing his process and weirdly shallow worldview, while smarties from the critical community are invited to express their misgivings about a white Jewish kid from Seattle whose ear-candy easy-listening sound seems a million miles removed from the Black musical tradition he’s coopted. Instead of taking sides, Lane respectfully assembles the rare movie capable of holding multiple ideas in its head at the same time. —PD

The Lost Leonardo

We’re in a renaissance moment of art-world documentaries — films that touch the intersection of culture, greed, fraud, and beauty — but of all the art docs that have come out in recent years, none achieves the big-picture resonance of Andreas Koefoed’s riveting aesthetic detective story. It’s about the mystery of the Salvator Mundi, a heavily damaged painting that was purchased for next to nothing at a New Orleans auction in 2005. But when it was brought to the New York art restorer Dianne Modestini, who retouched it to the point of repainting it, she declared, with all but definitive gusto, that it was a lost canvas by Leonardo da Vinci. The movie is about how the rest of the world (or enough of it, anyway) came to agree, but it’s really about the changing definition of art in a century where commodification has become validation. —OG

The Most Beautiful Boy in the World

In 1971, Björn Andrésen, a feather-haired Swedish teenager, was cast as the underage love object of Luchino Visconti’s “Death in Venice.” There had been youth idols before, especially in the rock arena, but Andrésen, hailed as “the most beautiful boy in the world,” became one of the cinema’s original media-age teen-god pinups. Kristina Lindstrom and Kristian Petri’s movie uncovers this fascinating slice of pop-culture history, but then it hauntingly shows us what became of Andrésen — the life of torment and loss, and resilience too, that turned him into a broken-down loner with the look of an ancient wizard. He’s far from the first child star to have found hard times as an adult, but his story is told with an elegiac empathy that allows him to stand in for all of them. —OG

President

In 2014’s “Democrats,” Danish doc-maker Camilla Nielsson already gave us one sensational fly-on-the-wall study of Zimbabwean democracy in halting progress. It was a story so patently far from over that we ought to have expected a follow-up, but Nielsson’s staggering docu-thriller “President” will blindside even viewers familiar with the embattled African nation’s recent history. Surveying in exhaustive detail the corrupt battleground of the country’s 2018 election — where the ruling ZANU-PF party prevailed in highly suspect, legally challenged circumstances — it’s a film both enlightening on its own intricate terms and chillingly resonant in a global, post-Trump political context. —Guy Lodge

Procession

American filmmaker Robert Greene has long used dramatization in documentary to disorienting, self-reflexive effect, whether speculatively probing the mindset of the late TV newswoman Christine Chubbuck in “Kate Plays Christine” or exposing the human rights injustice of a century-old deportation mission in “Bisbee ’17.” In “Procession,” his most monumental film, he brings the tools of performative drama directly to his subjects, as six victims of Catholic Church sexual abuse make their own short films to reenact and confront their trauma. It’s a challenging, discomfiting work with ultimately empathetic rewards — wrenching in its emotional impact, but never exploitative as it hands the power of creative process to these wounded men. —GL

The Rescue

The extraordinary filmmaking team of Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi takes you places you’d think it would be possible to go — like the side of the vertical cliff El Capitan in “Free Solo” — and where the logistical astonishment of knowing you’re there is outstripped only by the heart-stopping tension of what you’re seeing. Their latest feature is about the Tham Luang cave rescue, which took place in 2018 after a dozen members of a junior Thai football team, ages 11 to 16, were stranded more than a mile underground in one of the world’s most intricate caves, which had been flooded by monsoon rains. Rescuing them was a mission even Navy SEALs weren’t equipped to deal with. It was up to a freelance team of the world’s most elite cave divers, who devised a scheme of rescue so last-ditch audacious that to enter these claustrophobic nooks and crannies, and see it happening before your eyes, is to believe in both the human spirit and the miracle of human ingenuity. —OG

Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain

The great chef, writer, and television food explorer Anthony Bourdain lived a life that deserved to be celebrated, and Morgan Neville’s film pays tribute to Bourdain’s bad-boy artistry in ways that any fan of his will connect to. Yet it’s no exaggeration to say that there’s scarcely a moment in the movie that isn’t shadowed, on some level, by the mystery of Bourdain’s suicide. That such a life-force personality, seemingly in touch with (and in control of) the pull of his demons, could be plagued by despondency to the degree he was remains haunting, and the power of “Roadrunner” is that Neville doesn’t look for a simple explanation. Yes, even the famous, wealthy, and beloved can be depressed, but this movie tells the story of a charismatic but compulsive boundary-pusher whose desire to explore the ends of the earth left him, paradoxically, without grounding. —OG

The Sparks Brothers

You don’t have to love Sparks — and, in truth, I don’t even like them — to be fascinated and enchanted by Edgar Wright’s epic of fanboy music fetishism. The movie is devoted to the principle that Sparks isn’t just the greatest band you’ve never heard of but, in fact, a band whose greatness can be measured by the heroic obscurity of their one degree from stardom. Are Ron and Russell Mael, the brothers who make up Sparks, worthy of this awestruck veneration? If you think (as I do) that they had maybe half a dozen good songs on 25 albums, “The Sparks Brothers” becomes less a testament to under-the-radar masters than a kind of true-life Christopher Guest film: an unlikely celebration of how beauty, in certain strains of rebel pop, truly is in the ear of the beholder. —OG

Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)

There are thrilling concert clips throughout Questlove’s revelatory film about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, from the gospel majesty of Mahalia Jackson to the soul-pop elation of the Fifth Dimension to the radical fury of Nina Simone to the higher funk of Sly Stone. But the inner beauty of the movie is the way that these performances, coming on the cusp of Black Power, become so much greater than the sum of their parts. Questlove, reaching back into the history of each artist, creates an inspired tapestry of sound and image that shows you the meaning of this moment: how it channeled a freedom that was in the music, in the audience, in the rotating axis of history. —OG

Tina

The saga of Tina Turner is so famous that it’s become a kind of parable: the tale of a young woman of volcanic talent, whose marriage to Ike Turner became her catapult to fame and the source of her abuse, and how she escaped and reinvented herself as a middle-aged Black woman playing stadium shows, when almost no one in the music industry thought that was possible. Yet as you watch this film by Daniel Lindsay and T.J. Martin, you’re brought close to Turner’s life — the prison she lived in, the fire of her rock ‘n’ soul artistry — in a way that blows the roof off what we thought we knew. The film does full emotional justice to one of the most cathartic stories in the history of popular music. It also demonstrates why Tina Turner was a genius. —OG

Tiny Tim: King for a Day

You probably think of Tiny Tim as a freak-show novelty act: the leering, long-curly-haired elfin warbler, looking like a cross between Lord Byron and Nosferatu as he chirped “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” in his falsetto on “The Tonight Show” in 1969. But did you know that for several years, he was actually the biggest star on the planet? Johan von Sydow’s magical film shows us who Tiny Tim really was — a New York outcast named Herbert Khaury who always knew he was going to be famous, because he had a religious belief in the power of his oddity. Skewing gender, taste, and art itself, he became a global mascot and, as time went on, a has-been of postmodern melancholy — a journey the film spookily captures. —OG

The Truffle Hunters

There are more adventurous docs, but there are none more adorable than Gregory Kershaw and Michael Dweck’s delightful glimpse at lives — human and canine — spent foraging in the truffle-rich Piedmont region of Italy for the prized subterranean fungi. The film not only teaches you everything you never needed to know about truffles, aging, and a fast-vanishing, respectful relationship with the land we live on, it is also the best dog movie in recent memory. Certainly, by the time one sprightly octogenarian truffler vows to marry, just so his favorite pup will have companionship after he goes (he makes this promise during dinner to the dog, mind you), you too will be eating from its hand. —JK

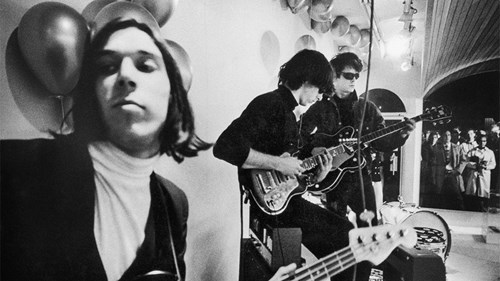

The Velvet Underground

One reason that no one ever made a full-scale documentary about the Velvet Underground, the incandescent godfathers of indie rock, is that there’s almost no concert footage of them. But Todd Haynes, in his luminous and indelible film, spins that disadvantage into a captivating aesthetic strategy. He has gathered every photograph and scrap of Velvets footage that seemingly exists, but he has also made a movie that captures how the band emerged from the soil of the New York avant-garde demimonde of the ’60s, which he evokes with a cinematic collage majesty that sears itself into your mind’s eye. The fateful symbiosis of Lou Reed and John Cale, of the Velvets and Andy Warhol, of fringe culture and rock culture becomes, here, a music doc as pure as a dream. —OG

The Rescue - Director of Photography: Ian Seabrook