by Charlie Heller, Polygon

“Film has tremendous balls,” Christopher Nolan told The Hollywood Reporter in 2015. “Film is oak, digital is plywood.” And even in an era where more films are shot on digital than ever, it remains a truism among everyone from Quentin Tarantino to Detective Pikachu’s cinematographer that celluloid offers a visual quality that digital simply cannot match.

Steve Yedlin disagrees — not just with this conclusion, but with the foundation of the debate itself. Cinephiles might know Yedlin as Rian Johnson’s go-to cinematographer on everything from Brick to Star Wars: The Last Jedi to Knives Out. But since the early days of digital, he’s also gained a reputation for his rigorous technical study of the science behind image creation.

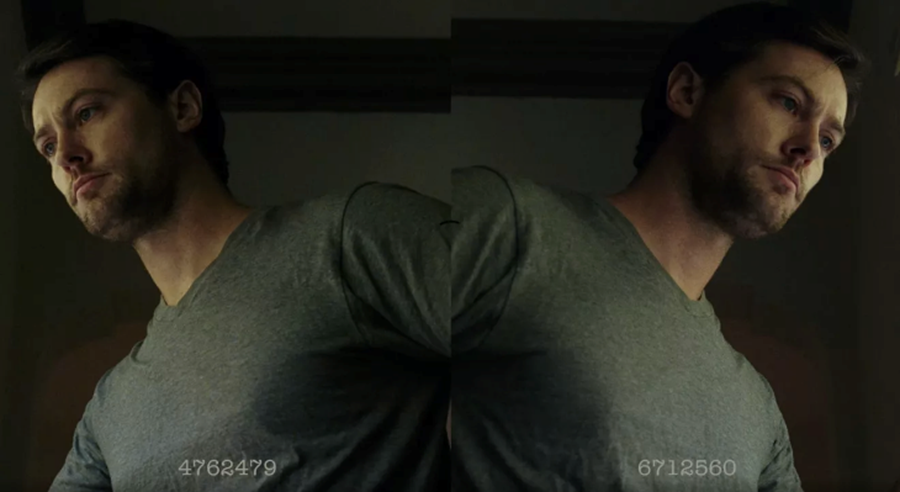

In April 2019, Yedlin released his scholarship’s latest fruit, the “Display Prep Demo.” An updated version of a video first released in 2015, the demo alternates between footage shot on 35mm film stock and a 4K Arri Alexa, industry standards for film and digital, respectively. Both have been processed to achieve what Yedlin says is “the look culturally associated with a traditional all-film system,” the kind people like Nolan say can only be achieved by actually shooting on film. Except, as Yedlin tells Polygon, when screened in theaters to an array of industry professionals, almost no one could tell the difference.

To anyone concerned with cinematography, the implications are huge: If you can make digital footage look convincingly like film, the debate over which format is visually superior is effectively moot. But for Yedlin, the first paradigm he hopes to change with his study isn’t actually about “film vs. digital,” but about how people think about cameras themselves.

A juxtaposition from the Display Prep Demo, which can be watched in full here. | Image: Steve Yedlin

‘THE CAMERA DOESN’T MAKE THE LOOK’

The thinking goes that if a cinematographer shoots the same thing with a film camera and then a digital camera, the two images will look different. Naturally, most people assume this is because each camera model has its own inherent “look.” But while the visual differences are real, Yedlin says, the cause is not the camera itself. If both cameras are of sufficiently high quality, they’re actually capturing the same visual data, regardless of whether they store that data as a film negative or as ones and zeroes.

That captured data is not the final image. A film negative is orange-y and inverted; ones and zeroes are … ones and zeroes. To get a viewable image, that data must undergo a transformation — either the chemical development process for film, or a series of mathematical calculations for digital. And it’s this transformation, not the initial capture (which is storing the same visual information), that results in the different looks associated with different camera formats and models.

If you change the chemicals used to develop film stock, the image will look different. There’s a similar alchemy for digital transformation: Change the math, change the look. In order to be usable, digital cameras need to have a transformation built in, so camera vendors supply factory-default math (stored as a “lookup table,” or LUT). But this math, Yedlin says, isn’t designed for a cinematic look, but for a “technical correctness” usually associated with “video.”

So when filmmakers criticize digital’s “clinical” look, they’re not necessarily wrong. It’s just that the cause isn’t the digital camera itself — it’s the camera’s factory-default math. Change those factory defaults to different math, Yedlin shows, and the image is literally transformed.

THE SECRET OF THE ‘FILM LOOK,’ REVEALED

To achieve the film look in the demo, then, Yedlin constructed his own math to transform the data captured by the digital camera into a result one would get from film. (For any filmmakers wondering, it’s mostly stored as a LUT on the camera that he simply turns on before shooting.)

To conceive that math, Yedlin also had to find an answer that is surprisingly absent from the whole film-vs.-digital debate: What is the look of film? Is it that film is, as Nolan says, better able to “reproduce color the way the eye sees it”? Or, as Yedlin has sometimes heard, is it all down to to the particularities of film grain?

“People tend to bounce around between ‘it’s exactly one thing’ and ‘it’s a completely ineffable thing you can never touch,’” Yedlin says, “but it’s actually a bunch of things.” In a 10-year process that brought rigorous scientific study to a field full of vague opinion, Yedlin became the first person to analyze and isolate the four ingredients that, together, create the classic film look: halation, gate weave, grain, and color rendition. And he’s made algorithms for each one.

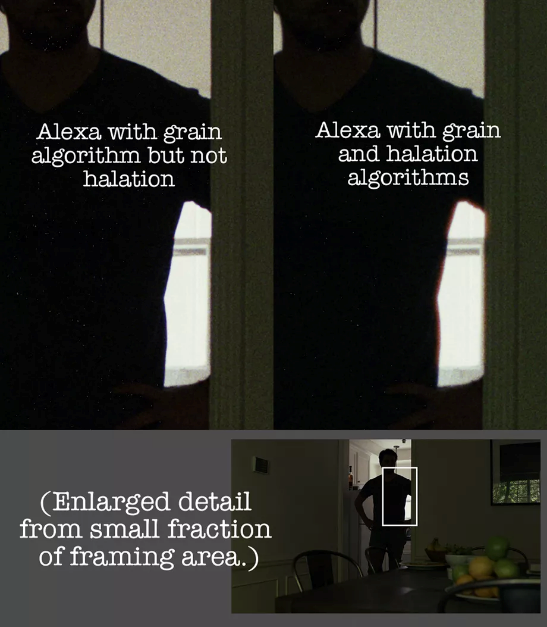

Image: Steve Yedlin

Halation is what you see at high-contrast edges — when a darker object is next to a much lighter one, like a person standing in front of a bright light. In images like these, the light bounces off the back of the film and hits a red layer, giving the edge of the darker object a blurry, reddish halo. (Despite it being one of the essential qualities of film, Yedlin claims that almost no one, not even experienced directors of photography, knows about halation.)

Gate weave is the slight unsteadiness from frame to frame caused by tiny movements in the film itself. For extreme versions, think of stereotypical old-timey silent films, where the image jumps around, or how old movie titles appear to vibrate.

Grain, the tiny, randomly generated particles that appear on each frame of film, is the one thing people do generally think about when it comes to the film look. Yedlin eschews the trend of layering a loop of grain scanned from a piece of film over digital footage. He has instead created an algorithm that uses probabilistic modeling to generate new grain that occurs randomly but within the same set of parameters as it does on actual film.

And then there’s color rendition. Simply put, it’s how the colors of the image look. But it’s also the most complex ingredient: The difference in color rendition between film and digital can’t be summed up as one thing like “more saturated,” Yedlin says, because it’s the sum of many differences. One might assume this means “more saturated reds” or “greens look more bluish,” but even that’s too simple. For example, the cinematographer says, it might not be that film’s reds are “more yellowish” than digital’s shades, but that they look the same until you get to a certain light level, at which point they get yellower and yellower.

There are so many complex examples like this that Yedlin had to gather “thousands” of data points to build a comprehensive model, as he demonstrates in this presentation. But however deeply you care to dive into the science of the classic film look, the fact that Yedlin has shown that you can understand it in specific, objective terms is another paradigm shift in one of filmmaking’s most passionate debates.

IT’S NOT JUST A DEMO

Rian Johnson has been as adamant a lover of classic 35mm film looks as Nolan and his cineaste contemporaries. Like them, he’s never wanted to shoot a movie that looks like anything else, from his indie debut Brick to his recent whodunit Knives Out.

But Knives Out was shot on digital cameras.

“For me, it was almost like an existential crisis, the choice of shooting digital on this one,” Johnson said on the Reel Blend podcast. “[But] from Steve [Yedlin]’s perspective, right now with imaging technology, there’s no reason that what you capture your image on needs to define the look of what you’re doing. What he told me over and over again is, it’s harder for him to make film look like film than [to] make digital look like film.”

Using the same display prep process as for the demo, Yedlin took the digital footage shot for Knives Out — almost all of it from the Arri Alexa Mini — and transformed it into something as effectively indistinguishable from film as it is in the demo, fully meeting the director’s exacting visual standards.

You might wonder: If it’s going to look like film, why shoot digital? “Because the camera doesn’t matter.” Yedlin says. “We can choose for logistics.” In other words: using digital cameras that are more reliable, precise, and versatile, and not having to ship film out and wait for days to get dailies back. With display prep, filmmakers also gained the ability to make very subtle tweaks to halation and grain, which are far easier to add to digital video in the amount you want than to remove from film footage.

Since there wasn’t an extra version of Knives Out shot on film for comparison, you can’t A/B test it like in the demo — though there was actually one shot done on film, with an old Panavision camera Yedlin had refurbished as a surprise birthday gift for Johnson. That shot was part of a three-camera setup, and, thanks to the display prep, it cuts seamlessly with the other two cameras, which were digital. But for skeptics, even that might not be enough.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi — film or digital? | Image: Lucasfilm Ltd.

Fortunately, there is one other major proof of concept, and you’ve probably seen it. “The Last Jedi is the biggest display prep demo of all time,” Yedlin says. While the majority was shot on film, approximately 50% of it was actually digital. And no, the digital shots aren’t the ones you’d guess — because you can’t guess. “They’re mixed in every which way,” he says, for reasons as simple needing another angle on a shot and not having any more film cameras available. Each time, film and digital are cut together seamlessly, sometimes even as cutbacks to the same shots.

Yedlin won’t mention any particular shots or scenes, but that’s the point — visually, you won’t be able to tell. In fact, he says, when looking at them in post-production, even he had trouble knowing which was which.

THE FUTURE

For 10 years, Steve Yedlin worked to break down and digitally recreate the look of film. But it was never the film look, just a film look. From Moonrise Kingdom to The Master, there are as many film looks as there are kinds of film, and each is made up of different combinations of the four elements above.

“THERE’S NO REASON THAT WHAT YOU CAPTURE YOUR IMAGE ON NEEDS TO DEFINE THE LOOK OF WHAT YOU’RE DOING”

Ultimately though, Yedlin’s hope isn’t that filmmakers just start slapping a film-emulation LUT onto digital and calling it a day. Rather, he wants them to realize that by understanding the components that actually create different looks, artists can become “authors” of their looks, instead of “shoppers” picking from limited off-the-shelf options.

He admits that this is a difficult process for anyone who either doesn’t have extensive technical knowledge, or access to a post-production house with people that do. But he believes that even just changing our mental model is a start. Instead of seeing cameras as paintbrushes, he wants them to be seen as measuring tools that can be shaped into anything with proper display prep.

“To me, it’s exciting for filmmakers to better understand the elements,” Yedlin says. “Right now, for most filmmakers, if they see something happening at the edges [of an object], they would be hard-pressed to know whether it’s halation, or a lens, or a filter.” If you know the pieces of a look that you like, you have more chances to achieve it yourself. Or, he says, to create new looks no one has ever seen before.

Yedlin provides two examples. Film’s edge halation is red, which creates an effect many cinephiles recognize and love. But why not make it green? Or white? While this is a subtle effect, the chance for variety opens up a whole new avenue of detail in image creation that remains virtually unexplored, more than a century after film’s creation.

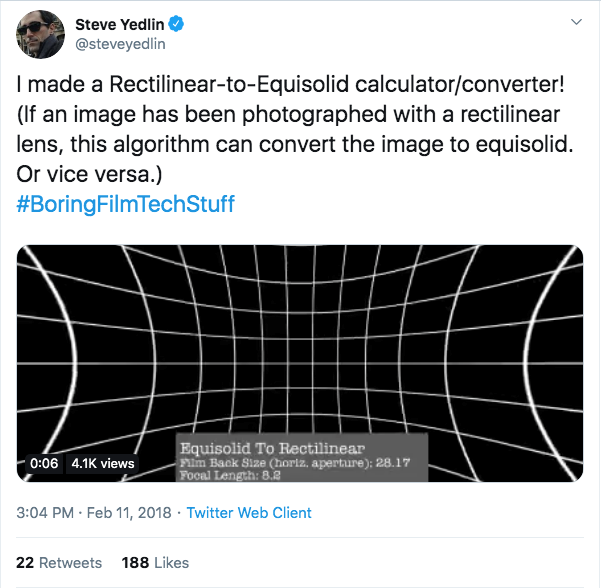

Full tweet here | Image: Steve Yedlin

The second example involves not the camera, but the lens. Many filmmakers love the distinct look of classic anamorphic lenses, which, to put it as simply as possible, create a more “widescreen” frame. Part of this is the type of curvature they give to the image, which Yedlin likes — but only when it isn’t too extreme.

So for the music video he shot with Rian Johnson for “Oh Baby” by LCD Soundsystem, he created an algorithm that adds that curvature, but only up to a certain amount. Then it stops. With lenses alone, this is physically impossible, but through analysis and modeling, he’s created a totally new kind of image.

While amateur filmmakers probably can’t replicate this at home, he says, it’s good to know that it’s possible. And if you are a professional, he adds, you still don’t have to become an expert on color science to get in on this new paradigm. The “difference between developer and user is not the same as the difference between author and shopper,” Yedlin says, and you “can partner with people and push vendors of all kinds, whether it’s software people or post-house partners, to investigate this stuff further, and push for new spaces in the marketplace.”

Considering that just a few years ago it seemed possible that companies would stop making 35mm film stock entirely, even the most die-hard celluloid lovers might want to get on board. Because Yedlin is offering a way out of the “film-vs.-digital” debate, and into a world where the visual choices filmmakers make aren’t up to the camera or format, but to the artists themselves.

Whether you’re a filmmaker who won’t make a feature without film, or one who wants visuals to look like nothing that’s come before, it’s a liberating prospect. As Johnson puts it, when shooting Knives Out, using the display process and paradigm:

“The medium did not define the look. We did.”