by Academy Museum

A new acquisition to the Academy Museum’s collection illuminates the long and eventful history of one of Los Angeles’ most important landmarks.

The Hotel Dunbar sign, recreated for Dolemite is My Name (2019), which is now part of the Academy Museum Collection. Gift of Netflix Inc. Photograph courtesy Clay A. Griffith.

Eddie Murphy was widely lauded for his appealing portrayal of real-life comedian, singer, filmmaker and actor Rudy Ray Moore in 2019’s Dolemite is My Name. The role was something of a comeback for Murphy who’s been rather quiet on our screens of late, but the film was also a love letter to 1970s Los Angeles, which is recreated in sumptuous detail through the production design of Clay A. Griffith and his team, as well as the stunning period costumes by Ruth E. Carter.

The beating heart of the film is the Dunbar Hotel, one of Los Angeles’ most important historical landmarks. We first encounter the Dunbar as a derelict building when Rudy goes in search of Ricco, a homeless man and self-proclaimed “repository of African-American folklore”, whose smart and foul-mouthed street poetry about a character called Dolemite has caught his ear. Brandishing some hooch, a wad of dollar bills and a tape recorder, Rudy sits and records Ricco and his friends attempting to outdo each other with their rhyming “toasts”. Gathered around a fire in the alley at the side of the hotel, they point out the Dunbar’s decaying sign and tell Rudy about its former life as Los Angeles’ “center of Black arts entertainment”, home to performers such as Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday but now inhabited by “junkies and winos”. The Dunbar is soon to make its own comeback, of sorts, when Rudy moves in and makes it the production base for a movie, starring himself in his hugely successful, self-created pimp persona of Dolemite.

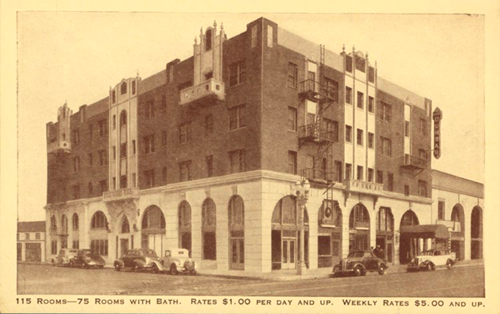

Historic image of the Dunbar Hotel, 1938 – or similar

By the time the real Rudy Ray Moore shot Dolemite at the Dunbar Hotel in 1974, it had been in decline since the 1960s. It was built as the Hotel Somerville (later re-named after poet Paul Laurence Dunbar) on Central Avenue in South Central LA in 1928, by John and Vada Somerville. The Somervilles were successful dentists and respected Black intellectuals who were active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The hotel was designed to provide high quality accommodation for Black people in the then-segregated city of Los Angeles, and it soon became a hub for African American political and cultural life. In its first year, it hosted the first NAACP West Coast convention and many prominent Black guests would pass through its doors over the subsequent decades. These encompassed civil rights activists, artists, actors, sportspeople, and musicians, including Ellington and Holiday, W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Lena Horne, Ella Fitzgerald, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Sammy Davis Jr.

The Hotel Dunbar was therefore a location laden with meaning and significance to the filmmakers of Dolemite is My Name. In a recent conversation, production designer Clay Griffith told the Academy Museum that it served as a “north star” during pre-production: “It all started at the Dunbar”. The hotel was the first stop for location research and while it happily survived some tempestuous decades and has now found new life as a residence for seniors, its soon became apparent that the building’s new function made it unsuitable for use in the movie. Nonetheless, the archival photos that line its lobby walls, and its famous neon-lit sign, were key to developing the look and spirit of the hotel for the film. Interiors were recreated in the studio, and location manager David Lyons discovered the Royal Lake apartments in Pico-Union as a suitable stand-in for the hotel’s exterior.

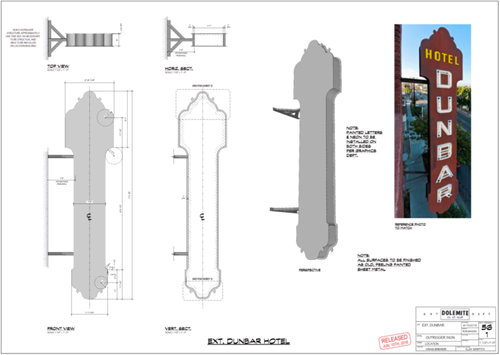

Art Department production drawing for the Dunbar sign, including a location research photograph. Courtesy Netflix Inc.

The sign being installed on the Royal Lake apartments. Photograph courtesy Clay A. Griffith.

Ironically, the Royal Lake apartments provided a closer match to the look of the Dunbar in the 1970s than the now re-purposed original. The illusion was completed by an all-important addition to the building: the vertical blade sign that extends down the side of the hotel. Griffith and his team created a scaled-up version of the original – the Royal Lake view was a taller building than the Dunbar, so the sign needed to be bigger to create the same visual effect. The 11’5” tall sign was built in-house by the art department, constructed in wood and then covered in tin. To give it the feeling of an old, peeling sign, scenic artist Damian Bowden spent weeks lovingly aging it with oxidizing chemicals and rubbing down layer after layer of paint. The finishing touch was the neon which sparks back into life when Rudy and his production team illicitly hook up the Dunbar’s electric supply in order to power their lights and cameras.

The Dunbar’s sign comes back to life. Dolemite is My Name (2019). Courtesy Netflix Inc.

The sign came to serve as a symbol the whole hotel and its history – a grand faded relic resurrected by Rudy and his film crew – and although creating signage is a standard part of an art department’s work, Griffith notes that he’d “never got to re-create one that has such historical value”. The Academy Museum is delighted that this beautifully executed production object is now part of the museum’s permanent collection, demonstrating the creative skill of Griffith and his team on Dolemite is My Name, as well as paying tribute to one of Los Angeles’ most significant cultural landmarks.

Hair and make-up from Dolemite is My Name will feature in Stories of Cinema when the Museum opens on September 30 2021.

A self-guided walk is available for those interested in seeing the real sign in situ, and to learn more about the Hotel Dunbar, Central Avenue and their role in Black cultural life in Los Angeles in the first half of the twentieth century.